It’s nearly the end of February, and we continue our journey through Edith Holden’s Nature Notes and Diary of an Edwardian Country Lady. This month, pussy willows, catkins, snails and snowdrops abound.

I spent most of February in Canada, where few were evident. Snow, snow and more snow. Back in the Cape for the last bit, I was heartened to see scatterings of snowdrops and daffodils shyly poking their noses up through the soil.

No bees are stirring on this side of the pond, though we have birds on the wing. They’re just beginning their morning chirping routine outside my window.

I was fascinated to learn that what we know of as “Groundhog Day” in North America is actually Candlemas Day, originating in Greece in the 4th century to celebrate the return of light. Candlemas, in turn, has its roots in the pagan holiday of Imbolc, celebrated from February 1 through sundown on February 2. In the Celtic tradition, the date marks the halfway point between the winter solstice and the spring equinox in Ireland and Scotland.

If Candlemas Day be fair and bright,

Winter will have another flight.

But if Candlemas Day be clouds and rain,

Winter is gone and will not come again.

Those are the same rules for Groundhog Day—if the groundhog sees his shadow, he gets frightened and goes back down into his hole, and we get six more weeks of winter. If it’s cloudy, he comes out, and winter is over.

Groundhog Day began in 1887 in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, when a newspaper editor from a group of groundhog hunters called the Punxsutawney Groundhog Club declared that Phil, the Punxsutawney groundhog, was America’s only accurate weather-forecasting groundhog. American crowds have gathered to watch successive generations of Punxsutawney Phils emerge from hibernation in Gobbler’s Knob, Punxsutawney on February 2 of every year since then. In Ontario, Canada, we have Wiarton Willie.

If you’ve ever wondered about Groundhog Day, it isn’t just a movie.

The plate and cup for February also feature primroses. Lucky Britain. Mine came from the grocery store—and are as welcome as any in the garden.

This month we feature Darjeeling tea to accompany a snack of Lemon Squares. Though technically a black tea, it’s delicately flavoured and the antithesis of enamel-stripping” “builders tea”.

The British started numerous Darjeeling tea plantations in India in the mid-1800s as alternatives to tea from China. After Independence, the estates were sold to businesses in India.

According to Wikipedia, the tea leaves are harvested by plucking the plant’s top two leaves and the bud, from March to November, a time span that is divided into four flushes. The first flush consists of the first few leaves grown after the plant’s winter dormancy and produce a light floral tea with a slight astringency this flush is also suitable for producing a white tea. Second flush leaves are harvested after the plant has been attacked by a leafhopper and the camelia tortrix [a moth] so that the leaves create a tea with a distinctive muscatel aroma. The warm and wet weather of monsoon flush rapidly produces leaves but they are less flavourful and often used for blending. The autumn flush produces teas similar, but more muted, to the second flush.

We tried the Darjeeling Premium Blend and the season’s Pick First Flush 2021 Darjeeling Blend. Both were delicious, though the First Flush blend had a more vegetal flavour, and I preferred the Premium Blend. An uplifting accompaniment to the lemon squares where a shortbread base holds aloft a silky smooth suspension of the tart lemon filling, a bit more” “cake-like” than lemon curd, thanks to the addition of some flour.

The first batch I made was, as we say, a hot mess. The original recipe called for pouring what amounted to liquid over the par-cooked shortbread base before putting the pan in the oven to bake. The liquid seeped under the shortbread base, leaving a gooey layer of lemon sludge on both the top and bottom—kind of a reversed shortbread-lemon filling sandwich. Frustrated, I googled” “lemon square sticky mess”. Apparently, this is a prevalent problem. Pre-cooking the filling until it thickens before pouring it over the mostly cooked base, then finishing it in the oven, solves the issue nicely.

That got me thinking about the prevalence of citrus in the winter months. We add lemon juice and honey to hot water to soothe sore throats; we take vitamin C to ward off colds. And historically, people have made marmalade from December through February.

Legend has it that marmalade was invented in Scotland by James Keiller (of Dundee marmalade fame, and for whom a certain Entertablement cat is named).

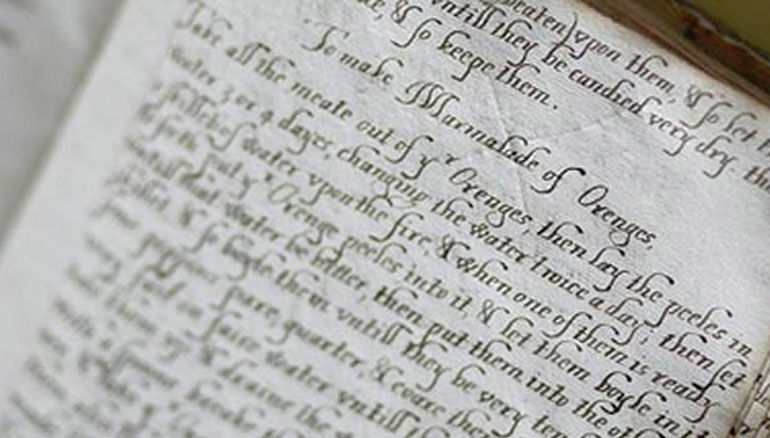

The story goes that Keiller received a cargo of disappointingly bitter oranges from Seville, and rather than making lemonade from lemons, his wife turned bitter oranges into marmalade. A tale of triumph over adversity, but sadly inaccurate. Food historian, Ivan Day, points out that Marmelet of Oranges can be found in a book of recipes from 1677 by Eliza Cholmondeley (pronounced “Chumley” – go figure).

Making marmalade involves transforming the bitter sharpness of citrus fruits, particularly Seville oranges, into a tangy-sweet jam-like spread, delectable as a topping for breakfast toast or tucked into sauces, puddings and bakery goods. Marmalade comes in many forms, the most popular styles being:

Coarse or Thick Cut where the peel is sliced into thick chunks for a tangy bitter flavour. Frank Cooper’s Original Oxford Marmalade is my favourite of that ilk.

Thin-Cut contains finely shredded peel resulting in a softer flavour and texture. My Dad was a big fan of Robertsons Silver Shred, a lemon marmalade with a delicate flavour and consistency. Robertson has co-opted the Marmalade-making-and-loving Paddington Bear image for its modern jars.

Anyone familiar with Rose’s Lime cordial may also enjoy enjoy Rose’s Lime Marmalade. Typical of a thin cut marmalade, the jelly is smooth and delicate, in which slivers of lime are suspended.

Vintage in which the marmalade is left to mature for a denser, richer flavour—Frank Cooper’s Vintage Oxford Marmalade is Glenn’s go-to variety. (For the curious, we take turns opening our preferred jars of marmalade, like semi-adults).

James Keiller may not have invented marmalade, but he has long had both the snazziest jars and a high-quality product. It’s one of my favourites. My Dad had a row of these old-style jars filled with various sizes of nuts and bolts on a shelf in his workshop.

The modern jars aren’t quite as pretty, but the marmalade is indeed marvellous. And not just because of Dundee.

In preparing for this blog, I researched what is involved in making marmalade from scratch. I’m thankful there are so many excellent commercial products on the market because it isn’t easy. First, one must cut all the orange peels into fine pieces (or shred them if you’re going for a fine cut).

A unique pot is needed—though if you’re an enthusiastic jam-maker, you may already be familiar with the Maslin Jam Pan. As described on their site, a heavy bottom dissipates heat for an even boil, and the wide, deep sides ensure an efficient and even evaporation as well as preventing too many hot splutters of boiling preserve.

Muslin squares are needed to gather pectin-rich pips and peel into bunches tied with kitchen string or a thick rubber band. Said bag is then suspended in the bubbling liquid and regularly squeezed to ensure sufficient pectin has entered the mixture for it to thicken. Then, to determine if the boiling mixture has reached the required temperature to reduce and “set”—220°F or 104.5°C—a variety of methods are suggested from a mysterious “wrinkle or flake test” to the more mundane (and probably accurate) use of a probe or candy thermometer. And let’s not get into all the sterilizing of jars, transferring of boiling liquid, etc.

As enticing as this picture is, I’ll stick to buying it with so many lovely marmalades from which to choose.

And that’s a wrap for February!

Stay warm, all. We will be back for March when I hope daffodils from the garden will grace the post.

Dear Helen,

The Sevilles and blood oranges are in the market now. In the 60s we used to get Rose’s lime juice without any sugar. Some time after the Cadbury purchase of Mott’s (not a nice company to work for), they started to add prodigious amounts of high fructose corn syrup, and the product was ruined IMHO. The history of the (Scottish) Rose company is fascinating. Their product was inspired by the need to keep sailors healthy with easy-to-preserve lime juice on their journeys (hence “limey”), and Rose patented the method. Oh, I hope the slugs don’t wake up soon…the daffodils are poking up now.

That’s fascinating, Beatrice. I didn’t know the history of Rose’s Lime juice, and just looked it up – very interesting. The Scots really did invent the modern world!

As with Cadbury’s absorption of Terry’s Chocolates from York, product quality really suffers when these behemoths take over. Quality Street and Terry’s chocolate oranges are not the same.

Hi Helen, I always enjoy your blog and look forward to seeing them in my inbox. I love the February plate and was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about it. Is it part of a set containing all 12 months??

Hi Katherine,

The plate is part of a set I picked up on Etsy earlier this year. It’s made by Heinrich H & C (now part of Villeroy & Boch) and has a 9″ luncheon or salad plate, cup and saucer for each month of the year, featuring illustrations from the matching month in The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady. My set has two Februaries and no August, but no big deal.

There is also set by produced from 1981/82 Caverswall; those plates are 10.5″ (dinner-sized) and have a lot more detail on the fronts and a description on the back.

I’ve added the respective links from Replacements so you can see what they look like.

So glad you’re enjoying the blog! Here is the link to the January blog on the Country Diary series, in case you want to read more about how this whole thing got started.

That’s interesting about ground hog day. What a story! I’m sure my snowdrops (that I brought from England) are up and I’ll miss them again. Just flowering almond and fruit trees in bloom now and beautiful. Enjoy the flurries ❄☃️

I’ll go over and check them out when we get back to the Cape, Maura. And send pictures. 🙂